Description

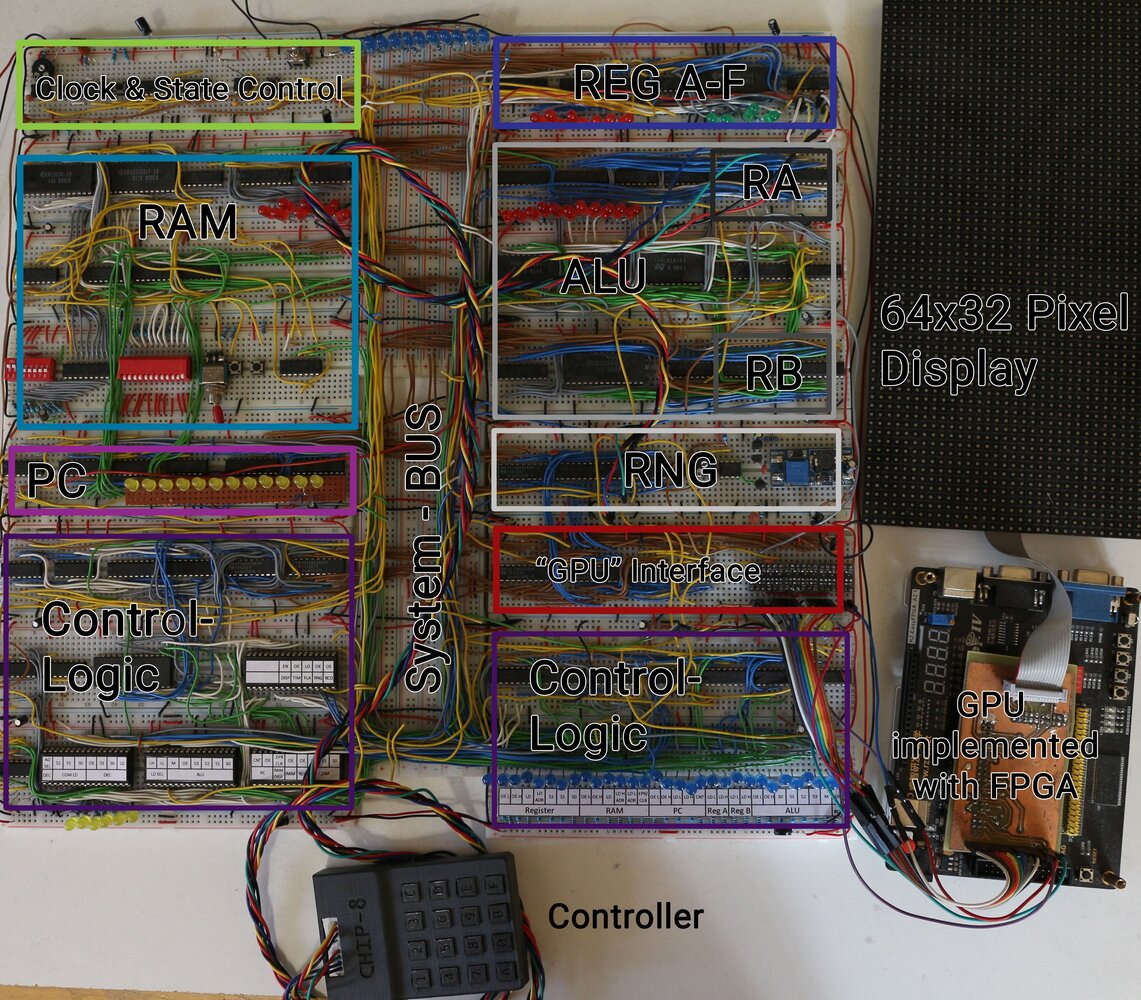

Chip-8 describes an “assembly-type” language as well as a typically interpreted virtual machine. I built a hardware CPU which is capable of executing these CHIP-8 instruction. This was a quite challenging task because I built everything as it came instead of having it perfectly planned in the beginning and some instructions are quite heavy-weight, where others are very simple. The tutorials of Ben Eater inspired me to build this CPU. Instead of following this tutorial step by step I built many components myself and sometimes consulted his videos if I was unsure how to solve something. Because of the “build as I go” mentality (partly because I did not understand everything in the beginning) the modules are not documented in detail which I really regret.

Very Useful Resources for Chip 8

- My goto reference for the instruction set http://devernay.free.fr/hacks/chip8/C8TECH10.HTM

- Awesome assembler, simulator,… https://johnearnest.github.io/Octo/

- Very clear tutorials for building a Breadboard CPU https://www.youtube.com/c/BenEater/videos

Caveats

- Because the whole build is based on breadboards the contacts are degrading with time — 3 years after I built it, it is still working, but sometimes glitches happen which is quite unfortunate.

- Chip-8 has some Instructions which are not well-defined. I settled to use the standard settings of the Octo project.

- I mostly built it with components I had on hand or that were easily available — therefore some choices were made because of availability and not because of simplicity or elegance.

- Because of limited space and money I sometimes combined parts of the CPU which should not be combined. For example, I used a single SRAM chip to store REG A-F (which itself is quite ugly already) as well as the 16 address deep stack.

- Looking at it after a few years I made many questionable choices during building it - which I surely made because of poor planning. But all in all it was a really awesome learning experience and I still love to look at the mess of cables, breadboards and chips which somehow work in harmony (more or less).

Modules

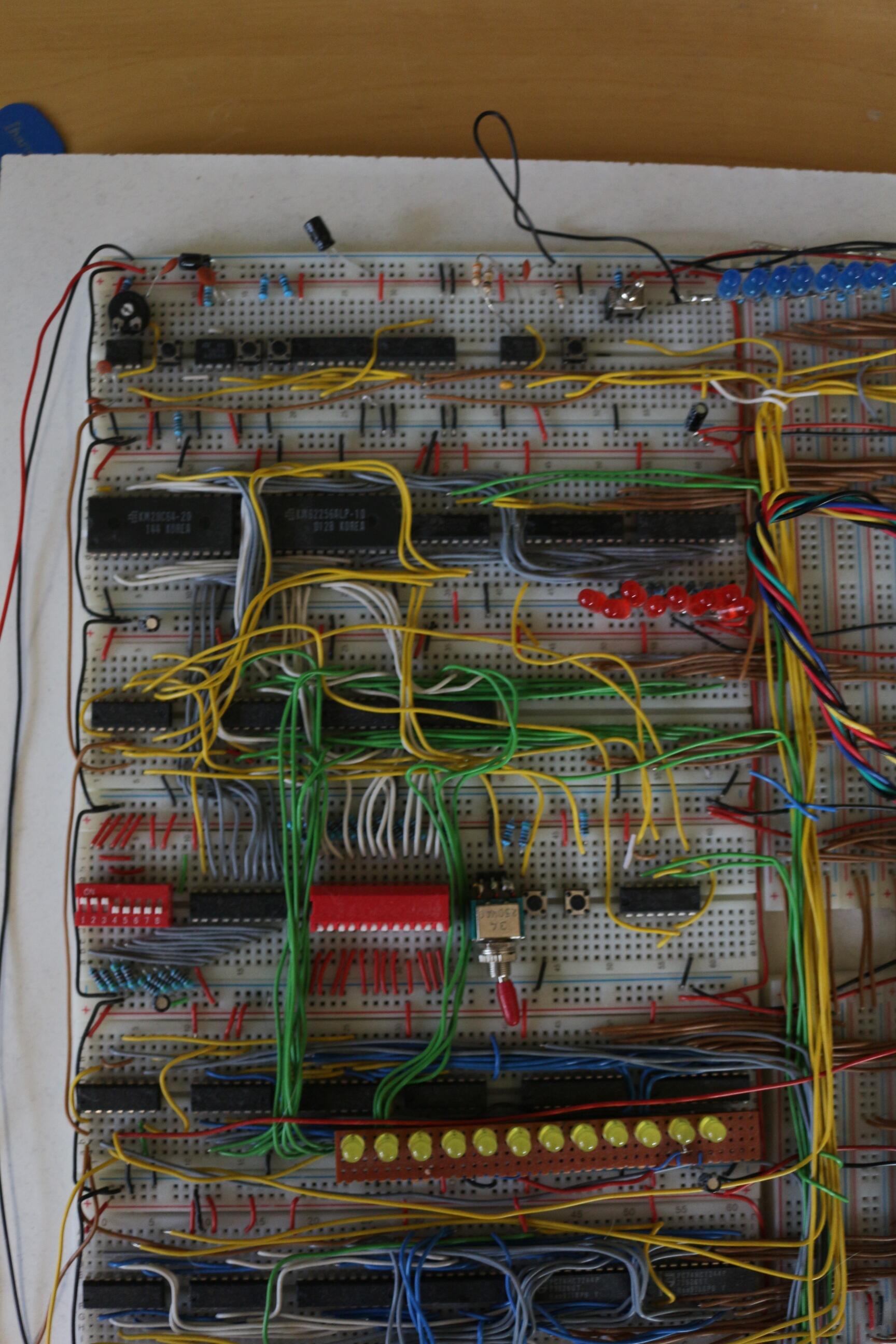

Clock & State Control

This is probably the easiest Module and very similar to the version of Ben Eater - it has an adjustable clock (astable 555) (~100Hz - 20kHz) as well as start and stop circuits. For the development process it also features a single stepping mode which uses a monostable 555 to generate pulses. A double-throw switch is used for program loading mode (which is explained in the RAM module). The last button on there is a reset-button which resets the PC and the microstep counter (inside the control logic).

Program Counter

The job of the program counter is to know where in the program we currently are. It mainly consists of 3 74HC193 which are able to count up and down (only the up direction is used). The output address is directly connected to the RAM (which is able to take addresses from either PC or BUS depending on a control flag). The PC can also connect to the normal system bus to load and output its content.

System-bus

Every word of data is transmitted over the main system bus located in the middle except the Program counter addresses (which is mentioned above). Each module is connected to the bus using 74HCT244 or 74HC245 tristate bus-drivers. This single bus is probably the biggest bottleneck but as it made interconnecting the components very simple (because the location of each module relative to other modules did not need to be known at all) it fit my “build as I go” style very well. The biggest regret I have with this bus is that I made it 12 bit wide. In the beginning of the project I thought that this is going to be useful because the address space of the CHIP-8 machine is 12-bit wide. But in the end I used the full 12 bits for only 2 or 3 instructions - which definitely was not worth the trouble in the end.

RAM

The main building block of the RAM is a KM62256 32Kx8bit SRAM. The RAM also features a KM28C64 EEPROM for loading the program into RAM. This program loading is achieved by switching a switch on the Clock&State Control and letting the CPU run for a few moments (less then 1/2 second) - contents from the EEPROM are copied to the RAM with every clock cycle.

The rest of the circuit (which mostly consists of 74HC157 Multiplexers) is used to manually program the memory which was used during development.

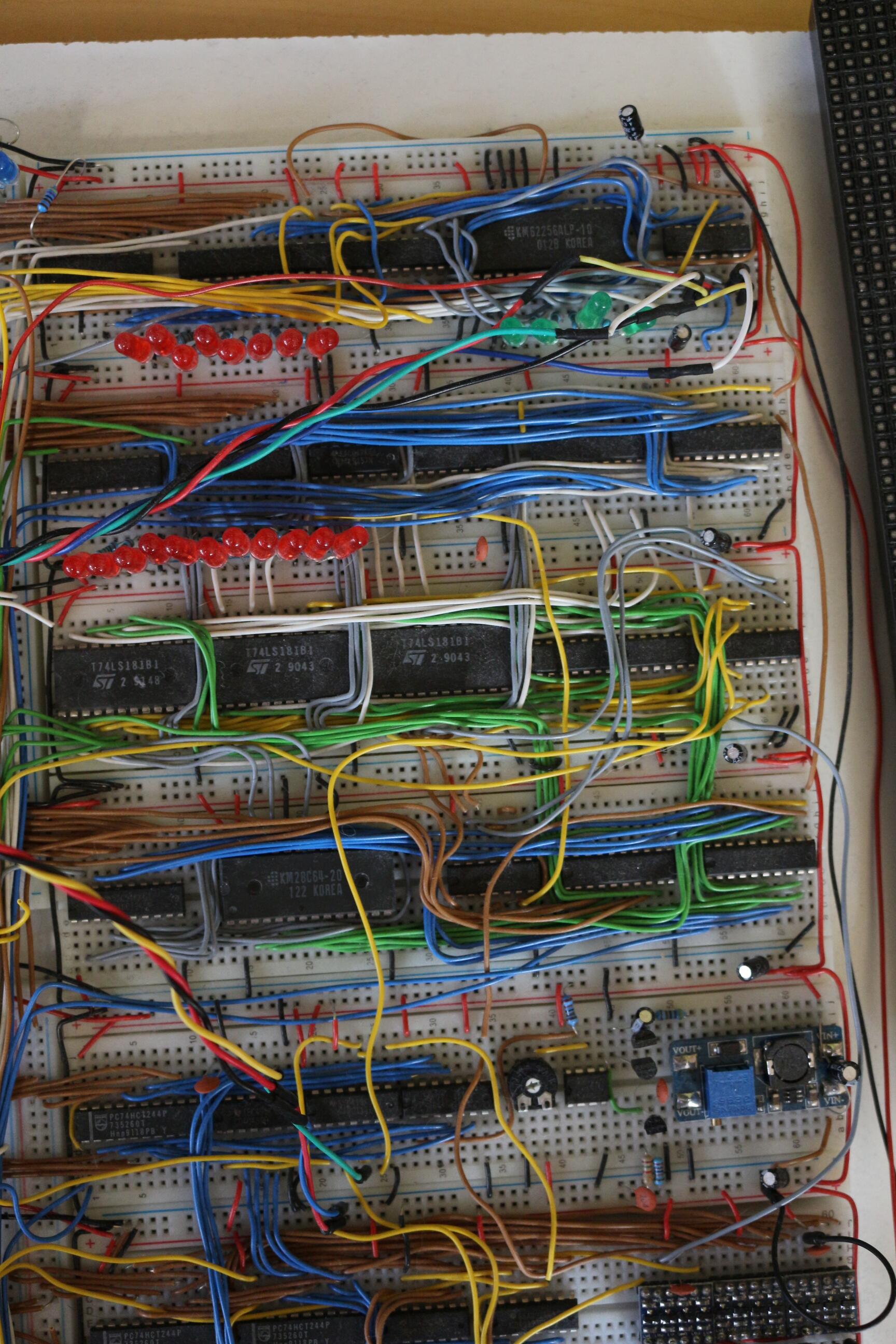

Registers A-F, Stack, Stack-pointer and Register I

Registers are the place where the CPU stores values to operate with. Normally, the registers are a lot faster than the RAM - but in my case this module also uses a single KM62256 (instead of single register chips for space reasons) to store the contents of registers A-F. The registers are told to load from, or output to the bus, by the control logic using three control signals.

The stack as well as the register I (12 bit Index-Register used for storing addresses) also reside inside the same SRAM-chip (which is a pretty ugly design choice, but it worked). The Stack-pointer is implemented directly in hardware using a settable counter 74HC193. The Stack-pointer was implemented as a counter, because this allows for a little quicker execution of RET and CALL instructions. A Multiplexer 74HC157, controls whether the stack-addresses or the register addresses are relayed to the SRAM module.

Arithmetic and Logic Unit

The 12-bit-ALU (12 bits for the same reasons as mentioned in the System-BUS part) uses the very useful 74LS181 chips for doing arithmetic and logical operators. It is accompanied by four 74HC377 to load and store the operands from the bus. Another 28C64 EEPROM is used as a “single operand ALU” to implement “esoteric” instructions such as LD B,Vx - “Store BCD representation of Vx in memory”. Simply using an EEPROM as combinatorial logic was the easiest and space-saving solution in this case I think.

Random Number Generator

This CPU actually uses a hardware-Random number generator. A simple LFSR would probably have been sufficient, but I decided to try and make a white noise generator which is sampled using a shift register. This analog circuit works well but is pretty sensible to the setting of the potentiometer which sets a decision level (whether the voltage is interpreted as 0 or 1). In hindsight, I would definitely go for a LFSR instead of this circuit.

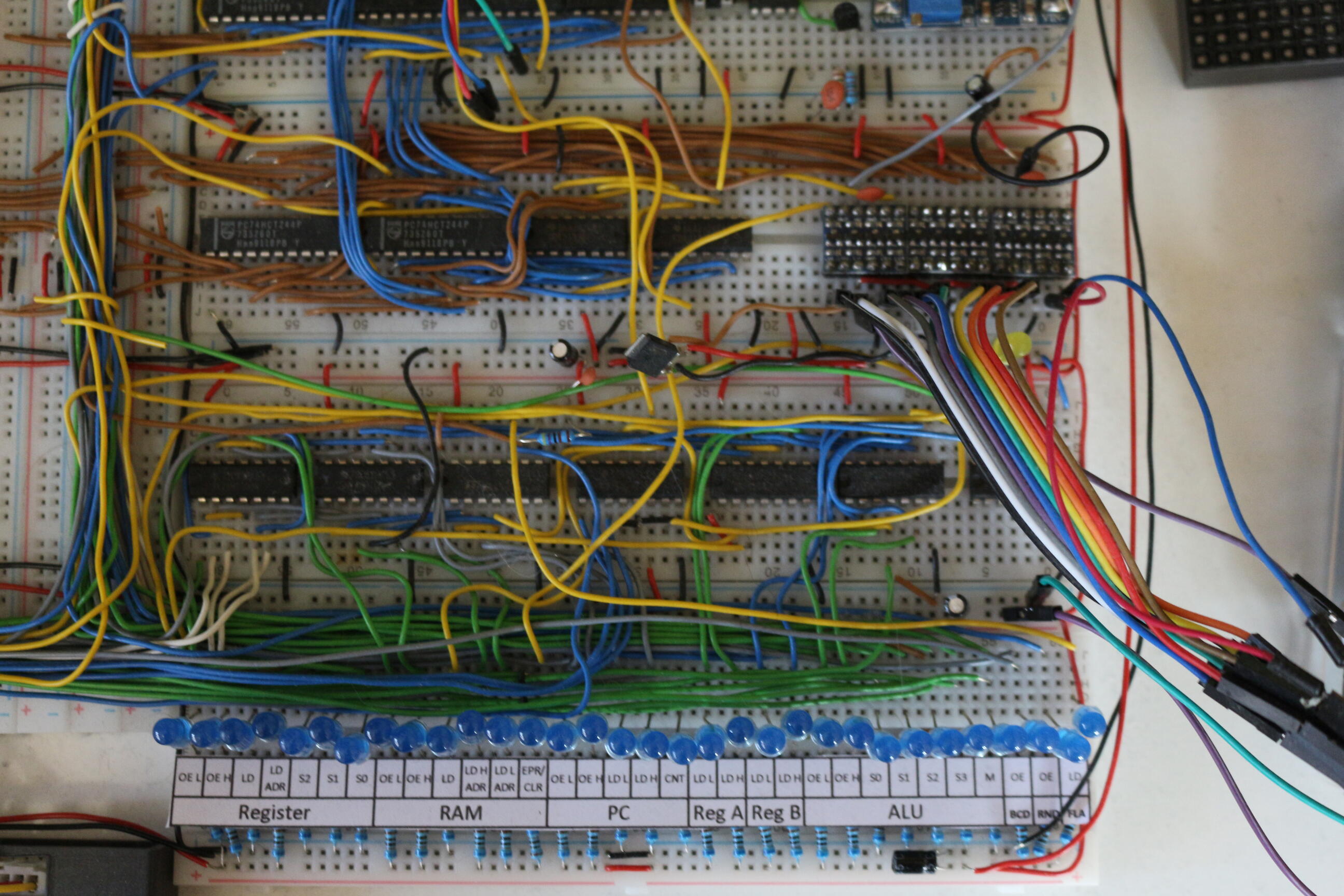

Control Logic

This was probably the most complex part to develop because the instructions of Chip-8 are formatted in a quite impractical way. One instruction always consists out of two bytes. The first 4 bits always indicate the type of operation - but the following 12 bits are quite universally used. Let’s say an instruction looks like this: Txyn where each letter stands for 4 bits in the instruction. Then n - part is sometimes used to indicate data, but also sometimes details the type of instruction. For example 8xy0 stores the value of register y into register x - but 8xy1 performs a bitwise or operation between the two registers. Another example where n is used for data is the instruction 4xkk which skips the next instruction if the register Vx != kk. The instructions also use many addressing schemes like immediate, direct and index addressing which further complicates decoding.

These issues were solved by using a few multiplexers and generic logic gates. The result of the “pre-decoding” done by this logic - a 6-bit code corresponding to each instruction, is then fed into four parallel flash memory chips SST39SF02 which store the microcode of the CPU. The whole CPU uses 31 control signals which are driven by 21 (partly combined) output bits of these memory chips. To keep track of the state of execution for the microcode, we need something similar like a Program-counter. The counter 74HC393 was used to keep track of the position in the microcode.

Because of some, quite hard to implement instructions, this counter was designed to count up to 63. The longest Instructions Fx65 - “Read registers V0 through Vx from memory starting at location I” (I is the Index-register) and Fx55 use a whopping 46 microsteps to complete. This is not typical at all - most instructions use somewhere around 7 microsteps (including 2 steps for fetching the instruction). The next section will show how this microcode looks like in my cpu.

Microcode

The microcode is used by the control logic to tell the modules what to do - step by step. We are going to look at an example instruction 8xy4 - “Add Registers x and y”. Typically, a CPU follows a fetch-decode-execute-cycle - my CPU does so too. The steps needed to be taken by my CPU to execute the addition instruction, are the following:

- Load first Instruction Byte

- Load second Instruction Byte - now the instruction is fully loaded and can be decoded

- Load Register x into ALU Register A (via system-bus)

- Load Register y into ALU Register B (via system-bus) - The ALU is told to add A and B by some control signals

- Output the result to the BUS and store back into register x

- Store overflow-value in VF (this is an example which shows why having all registers in SRAM was a questionable Idea)

- Done (start from step 1 and load next instruction)

Creating Microcode

To create the microcode I wrote a small Java application to transform a pretty basic notation of actions to memory maps for each of the four flash memories. It does not check if two actions are valid and simply sets the corresponding bits for each address.

The actual microcode I wrote for the Instruction described in Microcode looks like this:

//Vx + Vy , VF= Carry

x x 0: RAM OEL DEC LDH RB LDL PC CNT //RAM outputs to BUS, Decoder High Register Loads, Program Counter is Incremented

x x 1: RAM OEL DEC LDL PC CNT //RAM outputs to BUS, Decoder High Register Loads, Program Counter is Incremented

34 x 2: DEC Rx REG OEL RA LDL //DEC Rx lets the Control Logic select Register x, REG OEL tells the Registers to Output its content to the BUS, RA LDL tells the ALU Register A to Load (the lower byte)

34 x 3: DEC Ry REG OEL RB LDL ALU SUM //Same as above except Register y is selected

34 x 4: DEC Rx REG LDL ALU OEL ALU SUM FLA LD //Register x loads from BUS, ALU outputs to BUS, FLAG bit is loaded

34 0 5: DEC RF REG LDL BCD ONE BCD OE //If Flag was zero - RF is loading Value from Bus, BCD outputs one, BCD outputs one to BUS (BCD is the special EEPROM unit in the ALU)

34 1 5: DEC RF REG LDL BCD ZERO BCD OE //If Flag was one - RF is loading Value from Bus, BCD outputs one, BCD outputs zero to BUS

34 x 6: DEC RES //Control Logic Resets

The numbers in the front indicate:

- Predecoded value for the instruction

- State of Flag (x-Don’t care,0 or 1)

- Micro-instruction step count

All values containing x mean that any value in this bit must decode to the given control signals. That means one instruction must be written to more than one address in memory (which is once again used as ROM combinatorial logic). For example x x 0: ... corresponds to 64*2=128 addresses. The 64 comes from 2^6 possible decoded instructions, the 2 from the possible flag - states.

Everything that follows these numbers are Mnemonics which describe what the control signals should do. Every pair stands for a specific signal: e.g. RAM OEL means: module RAM - output to lower byte of bus. Many other examples can be seen in the code above.

Graphics Card

As mentioned above the GPU is implemented in an FPGA which handles the LED matrix as well as the communication with the CPU. Because the hardware required to drive the led matrix and interpret the CPU signals would be quite huge, I decided to use an FPGA instead of discrete components. Because I set out to build a CPU on a breadboard and not the entire system I think this is a good solution.

CPU side

There is only one instruction which allows writing to the display Dxyn - “Display n-byte sprite starting at memory location I at (Vx, Vy), set VF = collision.” This instruction takes 26 steps because it needs to push up to 15 bytes to the GPU. The basic protocol in which CPU and GPU communicate looks like this:

- (0-15) amount of Bytes to render to the display,

- x-position

- y-position

- Up to 15 bytes containing the displayed data

- If a bit cancelLED a one to a zero in GPU-memory (because the bytes are written using XOR) this is noticed by the GPU and a signal goes high. That signas is received by CPU and a flag is set.

CPU Microcode for drawing to the display

D x 2: PC OEHL RA LD

D x 3: PC LDL REG OEL COM REGIL DEC RF

D x 4: PC LDH REG OEH COM REGIH DEC RF

D x 5: DEC OE DISP LD

D x 6: REG OEL DISP LD DEC Rx

D x 7: REG OEL DISP LD DEC Ry

D x 8: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 9: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 10: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 11: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 12: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 13: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 14: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 15: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 16: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 17: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 18: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 19: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 20: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT

D x 21: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT ALU DISP

D x 22: RAM OEL DISP LD PC CNT ALU DISP FLA LD

D x 23: ALU DISP

D 0 24: REG LDL DEC RF BCD ZERO BCD OE

D 1 24: REG LDL DEC RF BCD ONE BCD OE

D x 25: ALU OEHL ALU A PC LD

D x 26: DEC RES

GPU side

The GPU is implemented in VHDL and runs inside an FPGA. Its job is to translate the protocol from above and set bits in memory accordingly. The memory contents are continuously drawn to the LED-matrix display. This is quite a demanding task because the LED’s need to be PWM controlled as well as multiplexed. Heart of the operation inside the FPGA is a dual-port RAM which allows reading and writing simultaneously at two ports. This is very useful because the CPU side and the LED-matrix side can be separated completely. One port can be used by the CPU side — which is comparably very slow. The other port can be used by the logic to drive the matrix. Controlling the process of multiplexing and PWM is handled by a Finite-state machine.

Results

I was able to run games such as Tetris, Pong and some awesome games from the Octojam. All in all I am very happy with the results and think the project was an awesome learning experience. If there were a second iteration I knew many things which I would approach differently, and I know what I would keep. If I had to set an approximate price tag for all components I would say that it cost around 300€ - which is not too bad in my opinion.